'Okinawa: The Stalingrad of the Pacific' (2005) by George Feifer.

When reading this book I was reminded of a quote from an historian I read years ago who said 'the two biggest losers of the second world war were Poland and Okinawa'. The first, the invasion of which had ignited the conflict in the first place, lost a quarter of its entire population, was left utterly devastated and under Stalinist rule. The second lost up to half its entire population, had most of its ancient culture and heritage obliterated and was destined to be used as a convenient military base by the two nations which had fought over it in 1945.

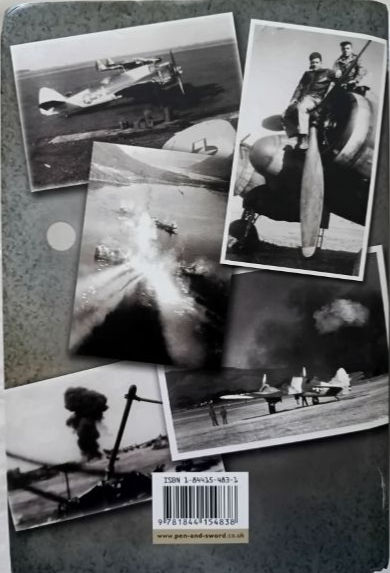

The Battle of Okinawa in April-June 1945 was incredibly vast and costly. To capture it, the Americans employed the largest invasion fleet of all time. Nearly 90% of all Kamikaze sorties in the entire war took place at Okinawa and what remained of the Japanese Imperial Navy sacrificed the world's largest battleship. Many historians believe that the campaign cost more lives than the two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined. The Americans lost over 20,000 men killed, the Japanese between 70,000 and 110,000 plus 10,000 Korean labourers and as for Okinawa's native population, anything between 40,000 and 150,000 people lost their lives. Some put the total death toll as high as 340,000. If the figure of 150,000 Okinawan killed is true, it represents half the estimated entire population of the island at the time.

Feifer does not write a linear, narrative history of the campaign but rather presents it in separate blocks, not necessarily in chronological order. He studies aspects of the campaign each in turn- the Yamato's final sortie, the Kamikazes, the fighting on Sugar-Loaf Mountain and the Shuri Line, the experiences of frontline soldiers, the sufferings of civilians etc. The book aroused some controversy as Feifer, although he gives ample attention to the many atrocities committed by the Japanese, also devotes a small chapter to those committed by American forces including the execution of Japanese POWs, the intentional targeting of Okinawan civilians and sexual assaults on female civilians that took place in the immediate aftermath of the battle.

However to his credit, Feifer seems determined to remain even-handed and he does not seem to seek to condemn one group more than another. He does however appear to be particularly sympathetic to the civilians of Okinawa, all too often forgotten in many other accounts of the battle. An ancient culture of gentle and isolated fishermen and farmers, the island was colonized by Imperial Japan in 1879 and the island's population adopted a kind of docile submission to their new rulers, encouraged by the island's elders.

When the US invasion commenced, many Okinawan people were pressed into military service, some willingly, many reluctantly. Any assistance they gave their Japanese rulers was seldom rewarded as many Japanese troops behaved appallingly towards them, using them as human shields, stealing their food, raping their woman and young girls and frequently insisting they take their own lives alongside Japanese soldiers who chose suicide. On a small, crowded island, many civilians found there was no-where to hide and as the fighting became more brutalized, war-weary American troops were not inclined to take the risk of checking whether it was hostile Japanese or starving, terrified Okinawan folk sheltering inside a cave before turning their flame-throwers or grenades into the interior.

It is not surprising that after Okinawa fell, there was little elation or joy among American soldiers. They only felt a dread for the invasion of mainland Japan which they thought was still to come and they wondered 'if Iwo Jima & Okinawa were this tough, what would Japan be like?' On the Japanese side, there was despair too. They had always viewed Okinawa as a mighty fortress and its loss arguably had as much impact on the Japanese decision to surrender as did the atomic bombs and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria.

I was impressed by this book. It was very evenly balanced and the author is not seeking to be revisionist, merely trying to present the grittier side of a campaign that previous historians have tended to overlook. It is not a pleasant book to get through and I must admit reading it may me quite depressed about humanity at times. But the final chapter on the legacy of the war on Okinawa today and the ability of its people to heal and forgive was quite inspiring.